How Docker Containers Are Just Linux

How Docker Containers Are Just Linux#

Modern containerization often feels magical — but at the lowest level, containers are not a new concept. They’re simply Linux processes running in isolation, packaged with their own filesystem and resource limits.

Let’s break this down using first principles and trace exactly what happens when you execute:

docker run -it ubuntu

1. What Happens When You Run docker run#

When you run that command, several layers of software are involved:

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Your Command: docker run ... │

└─────────────┬────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Docker Daemon (dockerd) │

│ ↳ Pulls Image │

│ ↳ Creates OCI Spec │

│ ↳ Invokes runc │

└─────────────┬────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ runc (OCI Runtime) │

│ ↳ Creates Namespaces │

│ ↳ Applies Cgroups │

│ ↳ chroot into rootfs │

│ ↳ Executes ENTRYPOINT │

└─────────────┬────────────────┘

│

▼

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ Host Linux Kernel │

│ ↳ Executes System Calls │

│ ↳ Enforces Isolation │

└──────────────────────────────┘

The result? You see what looks like a full Ubuntu environment, but what’s actually running is just a process on your host Linux kernel.

2. What’s Inside a Docker Image?#

Let’s inspect the Ubuntu image we just ran.

The filesystem inside an image typically contains:

/bin → Basic user binaries

/usr/bin → Additional binaries

/lib, /lib64 → Shared libraries

/etc → Configuration files

/proc, /sys → Virtual system filesystems

/home, /root → User directories

/tmp, /var → Temporary and variable data

That’s essentially a root filesystem (rootfs) — the minimal Linux environment required for user-space execution.

What it doesn’t contain:

- ❌ Linux kernel

- ❌ Device drivers

- ❌ Hardware-specific code

- ❌ init/systemd or background services

- ❌ GUI or desktop components

Hence, the Ubuntu Docker image is ~120 MB, while the full Ubuntu ISO is several GB.

So, the image is not a full OS. It’s a filesystem snapshot containing the userspace components of Linux — binaries, libraries, and configs — but without the kernel.

3. The Missing Piece: The Kernel#

Every running container shares the host kernel.

When you start an Ubuntu container on macOS (through Docker Desktop), it actually runs inside a lightweight Linux VM (since macOS doesn’t have a native Linux kernel).

On a native Linux host, containers directly share the host’s kernel. This is the key distinction between containers and virtual machines:

| Feature | Virtual Machine | Container |

|---|---|---|

| Kernel | Separate (guest kernel) | Shared (host kernel) |

| Isolation | Hardware-level (via hypervisor) | Process-level (via namespaces) |

| Size | Gigabytes | Megabytes |

| Startup Time | Seconds–minutes | Sub-second |

4. The Linux Primitives: Namespaces and Cgroups#

The container abstraction is built entirely on two Linux kernel features: namespaces and cgroups.

4.1 Namespaces: Process Isolation#

Namespaces create isolated views of global system resources. Each container runs within its own namespace instance.

| Namespace | Isolates | Example |

|---|---|---|

| PID | Process tree | Container’s PID starts at 1 |

| NET | Network stack | Own interfaces, IPs, routing tables |

| MNT | Mount points | Own filesystem mounts |

| UTS | Hostname & domain | Separate hostname inside container |

| IPC | Inter-process communication | Own shared memory, semaphores |

| USER | User/group IDs | Map container root to non-root host user |

| CGROUP | Resource view | Manages control group hierarchies |

When you inspect a container’s /proc tree, you’ll notice its process IDs, mounts, and networks are entirely isolated from the host — this is namespace isolation in effect.

4.2 Cgroups: Resource Control#

While namespaces isolate what a process can see, cgroups (control groups) limit how much it can use.

Cgroups are hierarchical resource controllers in Linux that manage:

- CPU shares and quotas

- Memory usage

- I/O bandwidth

- Network and PIDs

Example: Limit a container to 2 CPU cores and 4 GB RAM.

docker run -it --cpus=2 --memory=4g ubuntu

This translates internally to a cgroup configuration applied to the container’s PID namespace.

5. The Role of runc#

runc is the OCI reference runtime — the component that actually creates and starts containers.

Docker doesn’t “run containers” directly — it delegates to runc.

How runc works:#

- Receives OCI spec from the Docker daemon (

config.json,rootfspath, etc.) - Creates namespaces (

clone()with namespace flags) - Applies cgroup limits

- Performs

chroot()to the container’s root filesystem - Executes ENTRYPOINT as PID 1 in the new namespace

- Manages signals and lifecycle between host and container

You can actually run a container manually with runc:

runc run mycontainer

It’s the same binary Docker calls behind the scenes.

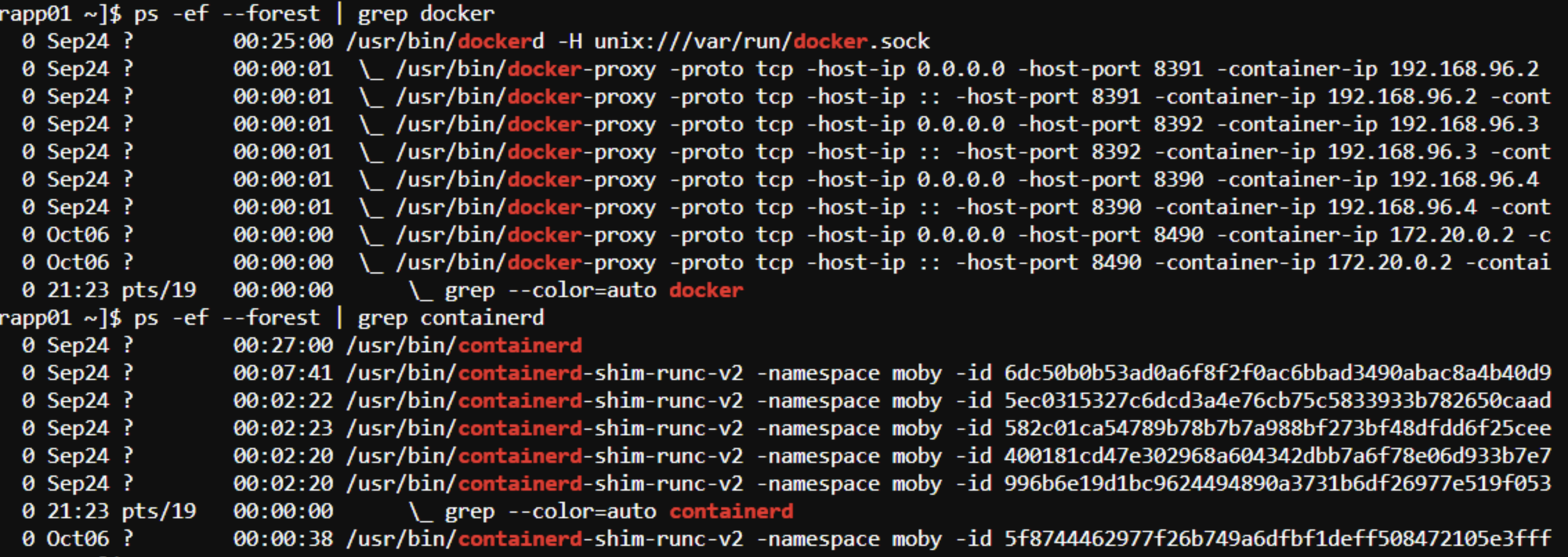

6. Container Daemon vs Runtime#

It’s crucial to separate the daemon and the runtime:

| Component | Function |

|---|---|

Docker Daemon (dockerd) | High-level management: image pull/push, build, logging, networking |

| Containerd | Mid-level orchestration of containers |

| runc | Low-level execution following OCI runtime spec |

The hierarchy looks like this:

docker CLI → dockerd → containerd → runc → Linux kernel

Each layer abstracts management, networking, and lifecycle, but runc is where containerization truly happens.

7. From Image to Running Process#

Let’s summarize the full flow step-by-step:

docker run ubuntudockerdchecks local cache; pulls the image if missingExtracts the image layers into a merged root filesystem

Generates an OCI runtime spec

Invokes

runcwith this specrunccreates:- Namespaces (

clone()syscalls) - Cgroups (via

/sys/fs/cgroup) - Chroot jail to rootfs

- Namespaces (

Executes

/bin/bashor the image ENTRYPOINTProcess now runs in isolation, sharing the host kernel

At this point, the container is just a Linux process with a restricted view of the system.

8. Why This Matters#

Understanding that containers are just Linux helps clarify:

- Containers are not lightweight VMs — they’re isolated processes.

- Portability comes from standardized rootfs + shared kernel.

- Security and resource isolation are kernel-level features, not Docker magic.

- Tools like Docker, Podman, or Kubernetes simply orchestrate these Linux primitives.

9. Formula Summary#

Let’s condense it:

Container = Root Filesystem (Image)

+ Linux Namespaces (Isolation)

+ Cgroups (Resource Control)

+ Shared Host Kernel

That’s all.

Every container technology — Docker, Podman, CRI-O, Kubernetes — builds on this foundation.

10. Closing Thoughts#

When you run docker run -it ubuntu, you’re not launching a new OS —

you’re launching a process jailed within Linux namespaces, constrained by cgroups, using the same kernel as your host.

That’s why containers are so fast, portable, and efficient.

In the next part of this series, we’ll explore Linux namespaces in action — creating isolated environments manually using unshare, mount, and chroot commands — essentially building a container from scratch.